Digital Eye - Homage

Harold “Doc” Edgerton – “A Man Who Froze Time”

Project Goal

A time-honored tradition for art students was to go to museums and copy work by the great masters. In fact, artists who became masters themselves began by copying the work of those they admired. There is no better way to learn about the decisions that artists make with respect to concept, composition, lighting, subject matter etc., than to replicate a work. However, you won’t be just replicating a work with this project. You will be going beyond that exercise to create an artwork that reflects the artist’s point of view and incorporates your personal interpretation of the artist’s work.

Introduction

Harold Edgerton, a U.S photographer and engineer was well known as the inventor of the electric stroboscope and as a pioneer of stop-motion pictures. He was one of the first photographers to successfully “freeze” time and capture the essence of visual facts within extremely brief durations. His lifelong works focused on one main theme – scientific inquiry into the intricate motions of objects that cannot be seen or detected by human eyes. Edgerton explained his motivation with the following quote, “Don’t make me out to be an artist. I am an engineer. I am after the facts, only the facts1.” Edgerton’s quote highlights how he wanted his works to be viewed as scientific research rather than as aesthetic photography. His background as a professional electrical engineer and professor at MIT, compelled him to view photography as a tool to assist scientific inquiry rather than a method to pursue artistic values.

Biographical Information

Harold Edgerton, was born in Fremont, Nebraska, on April 6, 1903 and was the first child of Frank and Mary Edgerton. He was raised in a small rural town far from modern technology. However, Edgerton showed great interest in technical matters involving cars, motorcycles, and electricity, and his father was able to support Edgerton’s talent at young age. For example, when Harold became interested in the town’s power plant as a high school student, his father helped him to get a part-time job at the plant. Harold Edgerton expressed this time as “great big belts, great big steam engines, all kind of meters and switches. A tremendous challenge, all kinds of things happening every day2.” This particular experience motivated him to pursue electrical engineering as his future career. It was also during this time that Edgerton showed his first interest in photography, encouraged by his uncle, Ralph Edgerton. Ralph was a professional studio photographer and taught his nephew the basics of photography. Even as an adult, Edgerton kept and treasured a darkroom safelight he purchased during this period. After high school, he attended the University of Nebraska and graduated in 1925 with an undergraduate degree in electrical engineering. It was his father who encouraged Harold to pursue a graduate degree, at MIT. However, he delayed entering MIT for a year in order to pursue an opportunity as a research associate at General Electric.

Though his experience at GE was interesting, the environment at MIT proved to be a more significant benefit as his research in photography and engineering resulted in the invention of the stroboscope, even though that happened quite by accident. While he was studying the problems of synchronous motors, Edgerton noticed that a tube he was using to create a surge of power flashed every time the power peaked. When the flash was adjusted to synchronize with the motor’s turning parts, it made the motor to look like it was standing still and that made possible the ability to capture on film a moment that the human eye could not see. In 1931, he earned his Ph.D., and his doctoral dissertation included a high-speed motion picture of a motor in motion using his own invented mercury-arc stroboscope3. It was such an innovative creation because during the 1930s, people still used explosive powders to create an artificial light source for photography4. Edgerton stated, “When I was a boy, I read with great interest but skepticism about a magic lamp which was used with success by a certain Aladdin. Today I have no skepticism whatsoever about the magic of the xenon flash lamp which we use so effectively for many purposes5.” Not only did this invention bring Edgerton fame as an engineer but also initiated his journey as a photographer. All of his photographic techniques, such as high-speed imagery, multi-flash, and rapatronic shutter, were based on the use of the stroboscope. Edgerton would not have been able to produce such unique pictures without first inventing the stroboscope.

Critique

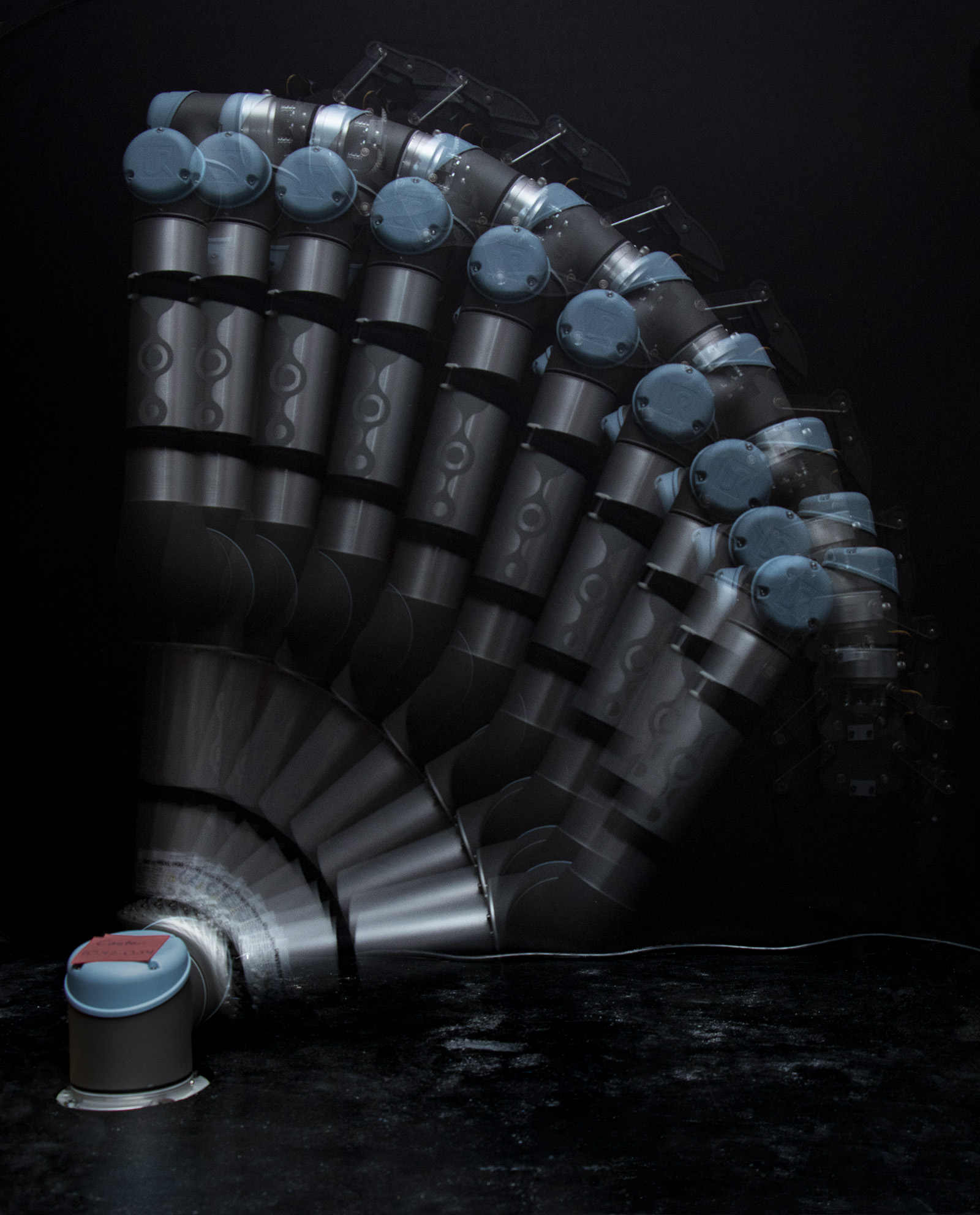

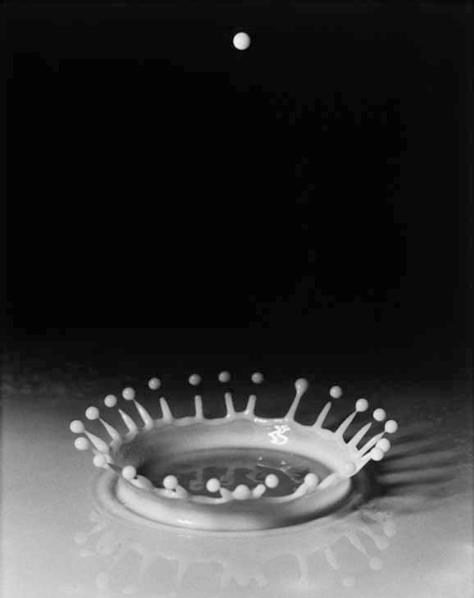

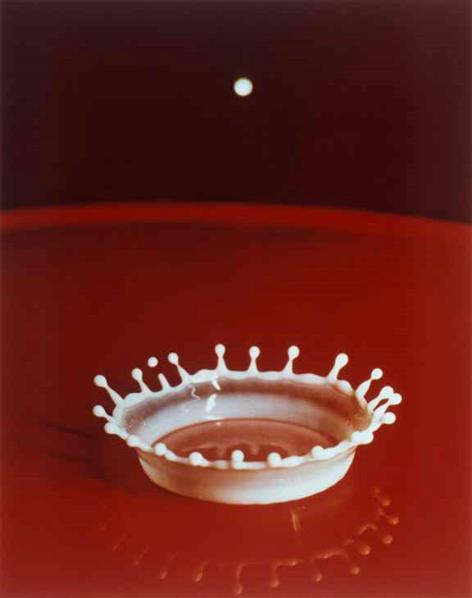

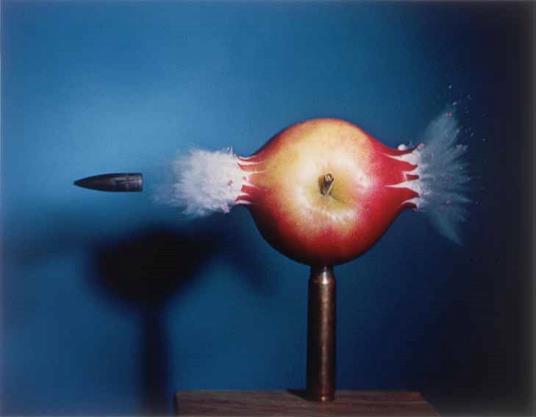

Roger R. Bruce, the curator/editor of the Harold Edgerton’s photographic journal ‘Seeing the Unseen’ stated, Edgerton is now best known to the public for the thousands of photographs he produced rather than all the inventions he created as an engineer6. This is ironic knowing the fact that Edgerton did not want to be called as an artist during his lifetime. His works are appreciated by the art world, gaining comments like “Consistently compelling body of work7”, and “Most remarkable time motion photographs ever made.8“The Museum of Modern Art included one of his most famous pieces of his work, a milk droplet, into the first photography exhibition held in 19379 (figure 1). Another of his most famous pieces, a bullet through apple10, (figure 3) is exhibited throughout the U.S, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum11. These exhibitions clearly demonstrate that his works are presented to the public as great pieces of artworks, although many people might not be aware of the scientific underpinnings. To quote photography historian Estelle Jussim back in the 1930s, “People had come to recognize and accept a new idea of the artistic12” through the magnificent pictures of Harold Edgerton. The ideas of Edgerton were something new to the engineering and art worlds and opened completely new horizons for both. With these “new ideas”, he inspired future photographers to delve into the aesthetics of stop-motion imagery. Even though people are now accustomed to his work, the unique aesthetic view from the earliest stop-motion pictures of the 1930’ and 1940’s continues to inspire contemporary artists.

Still Life versus Sequential Motion

Edgerton’s works are divided into two major contrasting themes: stop-motion imagery and sequential images of a subject’s motion. The biggest factors that divide these two themes are the different purposes and techniques. Edgerton utilized many different still life images as his stop-motion subjects, but most of the topics were focused on extremely fast objects such as a bullets, droplets, and popping balloons that are almost impossible to capture without the help of the proper tools. For stop-motion imagery, he synchronized his electronic stroboscope with a special high-speed camera and created a mechanism where only a single frame is captured for every stroboscopic flash. One of his most famous pictures, Milk Drop Coronet13 (figure 1, 2) is a great example of his work on stop-motion imagery. Milk droplets are common objects, but they fall too fast to visualize precisely. Freezing the moment of collision of a milk drop on to the surface, Edgerton was able to reveal the complex process of that motion over time. Bullet Through Apple14 (figure 3) is another great example of a stop-motion image, showing the intricate motion of bullet passing through an apple in a brief duration. For both pictures, Edgerton focused on one single incident during the event. This is the feature that is significant to stop-motion imagery, which differentiates itself from the sequential motion pictures. By concentrating on one incident, he was able to get clear details of the causes and results for each event, which would have been difficult for sequential images due to the tremendous amount of information they contain.

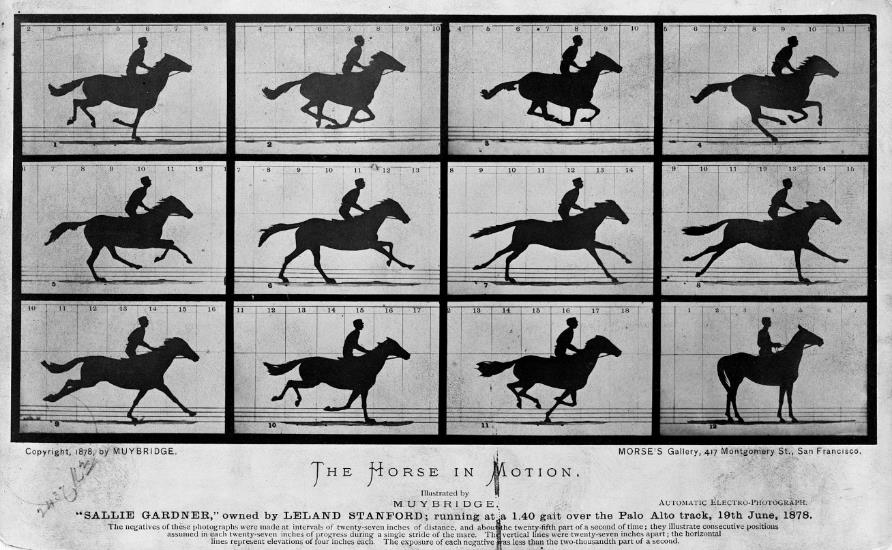

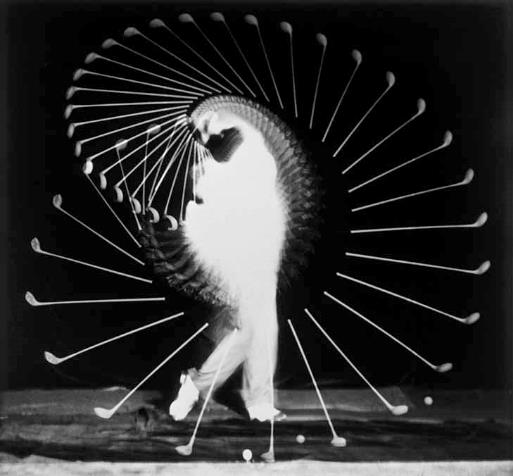

In contrast to his stop-motion imagery, Edgerton’s other works focused the study of the human motion in series. With the stroboscope, he adopted a technique called the multi-flash, which enabled him to take multiple frames of motions within a single frame. Setting up a long exposure time and flashing the stroboscope multiple times in a carefully controlled frequency, so that only the necessary movements were captured. Athletes were one of his favorite subjects. High-speed photography such as, Golf (1938)15 (figure 6) shows more than 30 steps during a single golf swing, revealing the tiny details of a fast-human motion captured within a single frame. Previously no one was ever able to or try to make such a picture in the history of photography so this was a major reason why Edgerton’s picture fascinated the public even without knowing the importance of the picture in the scientific community. However, taking a series of motions with the camera wasn’t a completely new topic. Edgerton’s predecessor, Eadweard Muybridge, made more than 100,000 images of stop-motion photography to study human and animal motion16. Famously he solved the question of whether all four feet of a horse were off the ground at the same time while it is galloping. The Horse in Motion (1878)17 (figure 4) was taken with an array of twelve different cameras triggered to make the exposure at almost the same time. As a result, Eadweard was able to capture the horse’s motion separately in twelve different pictures. The major flaw of this method was that each picture shows less detail about the entire motion, making it difficult to interpret the flow of the motion in the picture. However, as shown in high-speed photography, Golf (1938)18 (figure 6), each movement is distinctively recorded with a change of time and position, storing much more information and flow about the motion. Edgerton’s multi-flash method was widely used due to its simplicity in taking the picture and the amount of detailed information it creates with only one frame.

One interesting fact about Edgerton is that he kept contradicting himself by stating his pictures are only meant to be viewed as scientific inquiry, not as aesthetic photography. In fact, there are many clues that prove that Edgerton actually cared about aesthetic values of his photographs. The picture Milk Drop Coronet (figure 1, 2), is a good example. The writer of Edgerton’s biographical essay Douglas Collins stated, “But Edgerton was never satisfied with any of his early milk-drop images. For the next twenty-five years, Edgerton continued to take milk-drop photographs, until in 1957, he managed to capture a color image he liked19” While these photographs present scientific evidence, there was no need to take multiple pictures of the same object over duration of 20 years, since the scientific inspection was able to be done in the first experiment. The fact that he contributed his first version of milk drop picture to be exhibited at The Museum of Modern Art demonstrates his artistic pride in his photographs. Also, Edgerton’s use of photography in his later career when there was no apparent need scientifically seemed like an excuse to take spectacular pictures, such as Bullet Through Apple (1964) (figure 3). Douglas Collins again stated, “While these photographs present scientific evidence, for most viewers, their ultimate value is almost certainly aesthetic20” This sounds reasonable thinking of the carefully organized composition and exposure of the picture, which I don’t think is completely necessary for a scientific experiment.

My Personal Connection

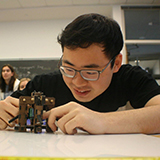

Harold Edgerton’s photography inspired me to delve into the topic of high-speed imagery. The fact that a specific millisecond is captured within picture photograph encouraged me to mimic his process as an artist. I set two goals: make a picture that is a scientific inquiry of moving objects, and try achieve aesthetic value with the image. My personal favorite picture was the Milk Drop Coronet (figure 2), so my first attempt was to take a picture of a milk drop by using burst mode on the digital camera. I quickly regretted my decision, because I realized I was simply trying to mimic Edgerton’s photographs. I looked for other ideas and found the picture Gus Solomons21 (figure 5). This particular photograph gave me the inspiration for the homage picture because of the wonderful arcs the subject creates with his arms, I decided to create a multi-flash photograph with an object Edgerton never tried before: a robot arm. Variations of shutter speeds and strobe frequencies were checked to make the view more intriguing. When the final composition was decided, the picture was taken several times to capture the right timing of the motion. I chose the picture where arms are aligned very neatly, which gave most of the information about the robot arm and had a marvelous artistic look.

In conclusion, Harold Edgerton was an engineer and artist who created wonderful “stop-motion” images that reveal the intricate motions of everyday objects. His inventions and techniques are still implemented today by hundreds of photographers, including me.

Homage Picture & Artist Statement

Harold Edgerton, an engineer and artist, made significant contributions to the understanding of human and object motion with his invention of the stroboscope. The instrument enabled photographers to capture fast moving objects and freeze motion by shooting multiple frames at high speeds, revealing the complexity of everyday movements. Intricate movements were concisely captured in each frame by the stroboscope, dividing the motion into several steps.

In this image, I attempted to follow Edgerton’s photography method using the multi-flash technique in order to capture multiple frames within a single photograph. I chose to focus on a unique motion of an object that Edgerton never studied during his lifetime: a robot arm. By programming the arm’s motion manually and controlling the frequency of the strobe light, ten detailed frames were captured within image, showing the arm’s distinctive movement as it travels. By mixing modern technology and the aesthetic aspects of a photograph, this image represents a modern outlook on Edgerton’s work. The art of scientific inquiry captured in a stationary time frame provides a fascinating view that Edgerton’s motion studies now moved even further to the stage of learning the machine movements.

Sources

-

Harold E. Edgerton, In Stopping Time: The Photographs of Harold Edgerton (1987)

-

Roger R. Bruce, Seeing The Unseen(1994)

-

Joseph Meehan, Capturing Time & Motion: The Dynamic Language of Digital Photography (2009)

-

Estelle Jussim, Stopping Time (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1987)

Reference2223

-

Harold E. Edgerton, In Stopping Time: The Photographs of Harold Edgerton (1987) ↩

-

Roger R. Bruce, Seeing The Unseen(1994), p.4 ↩

-

Studies at MIT: 1926 - 1931, The Edgerton Digital Collections(EDC) Project ↩

-

Harold E. Edgerton, In Electronic Flash, Strobe (1970), v. ↩

-

Roger R. Bruce, Seeing The Unseen(1994), p.viii ↩

-

San Jose Museum of Art, Into the 21st century: selections from the permanent collection, San Jose Museum of Art, May 23-September 12, 1999 ↩

-

Joseph Meehan, Capturing Time & Motion: The Dynamic Language of Digital Photography (2009), 33 ↩

-

Figure 3, References ↩

-

Estelle Jussim, Stopping Time (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.,1987), p. 32. ↩

-

Figure 1,2, References ↩

-

Figure 3, References ↩

-

Figure 6, References ↩

-

Figure 4, References ↩

-

Figure 6, References ↩

-

Estelle Jussim, Stopping Time (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1987), p. 72. ↩

-

Estelle Jussim, Stopping Time (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1987), p. 73. ↩

-

Figure 5, References ↩

-

Harold Edgerton’s Images are taken from The Edgerton Digital Collections Project Website ↩